On The Road

On The Road

by: Bill Oetinger 12/1/2009

Hell's Hairy Half-Dozen

Have you ever had this experience? (This is a rhetorical question: of course you've had this experience.) You're climbing a brutally steep wall, utterly maxxed out, and you look down at your rear derailleur to see if you have any more gears left. (You don't.) Then, a half-mile or mile later, still maxxed out, you do the same thing. You look again, as if maybe you missed a gear that last time you looked. Or you push on the shifter, in a vain, futile effort to find another gear that isn't there.

Some years ago, a few of us came up with a term for a really tough climb. We called it a Three-Look Hill. That means you shot that same, pathetic glance down at your cogs in the hope of finding that mythic, elusive, non-existent gear that would ease your load...once...and again...and finally again. (Pushing on the shifter lever when it's already tapped out counts the same as a look.)

You know, in your everyday, normal, functionally sane mind, you would never have to look more than once to know which gear you're in. But in the dire straits up on the mountain, with your brains no longer functional; with your brains in fact drooling out of your ear holes, such a settled, logical, rational grip on reality becomes as elusive as that mythic, missing cog.

Having noted this tendency to hunt for the lost cog--the cog that never was--I have tried to stop myself from looking; to use my steely firmness of character to rise above such delusional wishful thinking. I tell myself: "Stop it, you fool! You know you already looked. You know you're already at the top of the cluster...just get over it and keep pedaling!" But then another little voice might respond: "Yeah, but didn't I go through a little flat spot back there a ways? (Where the grade eased off from 16% to 10% for a few yards.) Maybe I dropped it down a cog (or two!)...? Huh? Maybe?"

It's hard to argue with that. Maybe I did! Couldn't hurt to look, right? So I do look, and--doh!--I have not shifted. I am still tap-city, and now I feel like an even bigger fool for having looked again.

This little mind-messer has been on my mind since I got back from cycling in the Alps. Travel is broadening in so many ways, and in this context, it has reminded me of the difference between the big climbs in the Alps and the little climbs in my own backyard, north of San Francisco Bay. We did quite a few of the big alpine cols made famous in the Tour de France. Two things that impressed me about them: first of all, they're big (as in long). Second, their gradients are relatively constant, from bottom to top.

Take Col de la Cayolle, for one example. (I choose it here because it fits my storyline, but also because it was the first real alpine pass we did, and it made a big impression on us. It also happens to be incredibly beautiful and loads of fun.)

You can check out Cayolle's elevation profile at the great website, Climb by Bike. According to this profile, the official climb begins in the town of St Martin-d'Entraunes. This yeilds a climb of 20.5 kilometers (12.7 miles), with 1291 meters (4234') of gain. But that's a slightly arbitrary spot to name as the start of the climb. One could just as well say it begins in Guillaumes and goes for 33 k (20.5 miles). It would only be a bit of stretch to suggest that the climb actually begins at the lower end of the Gorges de Daluis, 53 k from the summit, a climb of over 5800' in just under 33 miles. Almost all of those early miles are uphill, with just a few flats and mildly downhill dips here and there. Granted, the really hard work doesn't begin until the official profile says it does, but it almost all tilts up and it most assuredly all adds up. Big!

Then there's the question of gradient...steepness. Most of the time, alpine climbs have moderate grades, and most of the time, they're fairly constant. I know: there are any number of exceptions to this; lurid, brutal pitches that will destroy riders. But in the main, the long, steady grade is the rule. Climb by Bike uses a nice, simple, color-coded graphic to display gradient. 0-4% is green, 4-7% is blue, 7-10% is yellow, and over 10% is the appropriately colored red zone. Cayolle's profile is mostly a blend of blue and yellow zones with some green and just two little snips of red, very short. (I remember them!) It all averages out to 6.3%. So although the climb is absurdly long, it is rarely all that steep, with the end result being that one can just sit there and twiddle away at it and eventually roll over the top without being wiped out by the effort. (It would of course be different at race pace.)

But this column isn't really about the Alps. It's about our backyard hills...the ridges and valleys and pocket canyons we ride every week. The Alps simply serve as the contrast to what we have here, and thinking about those climbs helps define the nature of the North Bay climbs and understand how they differ from that classic, alpine paradigm we all have come to know from le Tour.

Our climbs are different in both the ways listed above. They are rarely big (long). The longest continuous climbs we have in the North Bay are about five miles...a bump by alpine standards. But what they lack in overall size, they make up for--to some extent--by their gradients. We certainly have some moderate, constant grades. But we also have many that are very steep. Most of all, we have a lot of what I call Chutes-and-Ladders climbs.

Remember that childhood board game, Chutes and Ladders? You rolled the dice and moved your piece up the meandering mountain path. If you landed at the foot of a ladder, you got to climb quickly to a higher tier on the trail; if you landed at the top of a chute, you would take a downhill plunge, back to where you had been before. (There is something slightly counterintuitive to this construct, it seems to me, at least from the point of view of a cyclist, and I should think to the mind of child as well. After all, we all like going downhill, letting gravity have its way with us, whether it's carving a mountain pass or slipping down the slide at the neighborhood park. In the game, the chutes are Bad, because they set you back, back down the hill, so you have it all to climb again. That assumes that getting to the goal--winning!--is the most important thing, a traditional, conservative value the game is no doubt promoting. But if the journey is more enjoyable than arriving at the goal, then what the heck, go down all the slides life puts in your path.)

But I digress. (Too many chutes in my path, probably.) The reason I call our climbs Chutes-and-Ladders is because, frequently, they go down and much as they go up. Excuse me? How can a climb go down? Well, they don't, but what we have here, in this region, is not single, monolithic climbs that go for miles, with one, clearly defined summit. What we have is sections of undulating road that amount to a single challenge but are made up of many ups and downs, all bundled together...chutes and ladders, ladders and chutes, up, down, up, down...all day long. And if you think a series of small, steep climbs can't beat you up just as throroughly as one big, steady climb, then obviously you haven't ridden in the North Bay.

And that brings me back to my original anecdote about the Three-Look Hill...to the wheedling little voice that says: "Yeah, but didn't we go through a little flat spot back there and drop a cog?" It turns out that such mind-messing questions are not unwarranted here, because in all likelihood, you did go through a little flat spot or even a little downhill. Because that's what the roads do here (and what they do not do in the Alps or the Rockies or any of those big-mountain regions). In the Alps, you can find a rhythm and keep plugging away..."tapping out a tempo," as Phil Liggett would say. And because the grade is constant, you know what gear you're in. You're never going to look three times to see if you have another cog.

But in the chutes and ladders of the North Bay, no way. Nothing stays the same for more than a mile. Even on a longer climb of a few miles, there will be several changes in grade: those little false-flat shelves where you just might have dropped it down a cog. Sometimes those little breaks are a mercy, but most of the time, they just mess with your head. You begin to think the worst is over and then, blam, up goes the pitch again. If Climb by Bike had our North Bay climbs on their site, the constant up-and-down nature of the roads and the endless gradient shifts would make their color-coded graphic look like a rainbow: all four colors flashing on and off, several times a mile.

So anyway, to try and lend some color and texture to these unique and challenging North Bay hills, I am going to present thumbnails for my Hell's Hairy Half Dozen: six of the gnarliest, funkiest climbing packages in the region. Two are relatively small, two are medium, and two are big. All are serious work. I'll proceed from shortest to longest...

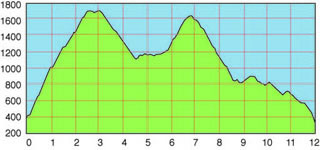

• Coleman Valley, from Hwy 1 to Occidental. 10 miles, 1633' of gain.

Coleman Valley has appeared in both the Coors Classic stage race and the Tour of California. It also is the last big challenge in the recent and much publicized Levi's King Ridge Gran Fondo, which followed most of the route of that old Coors Classic stage. It also appears as one of the bigger challenges in the Mount Tam Double Century, coming at around 125 miles. (They turn off of it with a couple of miles to go, and their next road--Joy--is every bit as hairy as any part of Coleman Valley.) Our club uses Coleman Valley as part of the 200-k loop on our Wine Country Century, although we go toward the coast instead of inland from the coast. The last big descent to Hwy 1 is so steep and tight and exposed, we have a person in a skeleton costume out there, warning the riders to dial it back a notch. It seems to be working: we haven't had a bad crash yet.

Coleman Valley has appeared in both the Coors Classic stage race and the Tour of California. It also is the last big challenge in the recent and much publicized Levi's King Ridge Gran Fondo, which followed most of the route of that old Coors Classic stage. It also appears as one of the bigger challenges in the Mount Tam Double Century, coming at around 125 miles. (They turn off of it with a couple of miles to go, and their next road--Joy--is every bit as hairy as any part of Coleman Valley.) Our club uses Coleman Valley as part of the 200-k loop on our Wine Country Century, although we go toward the coast instead of inland from the coast. The last big descent to Hwy 1 is so steep and tight and exposed, we have a person in a skeleton costume out there, warning the riders to dial it back a notch. It seems to be working: we haven't had a bad crash yet.

Going the way the races have gone, the worst comes first, as the road kicks up 800' in the first 1.5 miles, switchbacking up the steep mountainside before leveling off for a run along the ridgeline. More climbs follow--less severe this time--and the road tops out at 1100' among high, sheep-cropped meadows and stately stands of huge old oak and bay trees.

Give one last, backward glance to the panorama of ocean and coastline and then plunge downhill between split-rail fences on a steep, technical dive through the woods into the pretty little valley that gives the road its name. That's the road's first real chute, and it's a wicked one: a 15% plummet through the trees, on sketchy pavement, with a tight right-hander midway down the descent that will eat you alive if you're not careful. That's what happened to Dave Zabriskie the first time the Tour of California did it in 2007. The corner ate him up and that was the end of his Tour. It almost took out Mario Cipollini the next year. Graham Watson got a great photo of the Lion King, off in the dirt on the outside of the corner, just barely hanging on. (I tried to find the photo on-line, but Watson no longer has it available.)

After that perilous chute through the woods, the road kicks up in another ladder, and after a scenic run along the ridge, ends up with one more fast, kinked-up descent into the town of Occidental. When we descend into town, we have to stop at the stop sign at the bottom of the hill, but when the racers do it, they hit that corner going fast, and they have to rail around a 90° bend, at speed, in a pack. Hairy...

• Fort Ross, from Hwy 1 to Cazadero. 12 miles, 2050' of gain.

Fort Ross is best known in the bike world as the last big challenge in the Terrible Two Double Century, coming at around mile 165. It's similar to Coleman Valley, in that both climb up from the coast--very steeply--both have two significant summits, and both have an assortment of hairy, white-knuckle descents that can hurt the unwary or over-amped rider. It's just a bit bigger and more extreme than Coleman Valley in every respect.

Fort Ross is best known in the bike world as the last big challenge in the Terrible Two Double Century, coming at around mile 165. It's similar to Coleman Valley, in that both climb up from the coast--very steeply--both have two significant summits, and both have an assortment of hairy, white-knuckle descents that can hurt the unwary or over-amped rider. It's just a bit bigger and more extreme than Coleman Valley in every respect.

Most riders in the Terrible Two are prepared for a battle when they get to the rest stop at the beginning of Fort Ross Road, across the highway from the old Russian fort. They can see the first steep wall from the rest stop. It's 2.6 miles and averages 11%. But it is never average. It varies from 3% to 15%...a typical North Bay profile. It's always a hard climb, but coming where it does in the TT makes it even harder, and that's the Fort Ross most riders know: the one from their TT experience. What most riders aren't prepared for is the second climb on Fort Ross: Black Mountain. After a twisty, tangled descent of a mile-and-a-half and then a mile of little lumpy stuff in the canyon, Black Mountain climbs about 500' in a mile. Not a brutal climb, really, but it's a psychological brick upside the head for a lot of people. They got up the infamous Fort Ross climb; they thought they had it licked...and then here the damn road goes jacking up the effing canyon wall again. I know it has been the end of the line for a few folks...a ridge too far.

And then there is the long descent from Black Mountain to Cazadero. Most of the time, for most riders, this is big fun. The hardest climbs are over and it's gravity candy, full speed ahead. But it's another of those nasty chutes: very tight, very technical, very poor pavement, and lots of booby traps hiding in the dappled shade. You could build a nice little picket fence alongside the road here with all the broken collarbones this descent has produced. If the ladders don't get you, the chutes will.

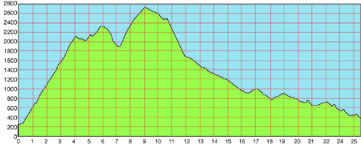

The Geysers: from Red Winery to near Cloverdale. 25.5 miles, 3500' of gain.

This too is a monument on the Terrible Two. It's the biggest challenge of the first half of the ride, with the riders turning onto the road at about mile 70. The first climb is one of the longer climbs in the North Bay at around four miles, and for this region, it's fairly constant. Not absolutely constant: there are all sorts of false-flats and mini-walls mixed together, but generally, it's steady...and pretty dang steep, like about 8-9% on average.

This too is a monument on the Terrible Two. It's the biggest challenge of the first half of the ride, with the riders turning onto the road at about mile 70. The first climb is one of the longer climbs in the North Bay at around four miles, and for this region, it's fairly constant. Not absolutely constant: there are all sorts of false-flats and mini-walls mixed together, but generally, it's steady...and pretty dang steep, like about 8-9% on average.

Over that first summit, at Hawkeye Ranch, there are two miles of rollers and a little climb, then a fast descent of a bit over a mile into the canyon of Big Sulphur Creek. Then things get ugly. This second big climb is only a mile-and-a-half, but the first mile is well over 10%. It's also all out in the sun, which can be an issue on a hot day. It eases off a little near the summit, which is the highest paved road in the county at about 2700'.

It's strange to think of a place where the highest road is only 2700' above sea level as being a butch climbing venue, but this area certainly is. Many pros train here in the winter because these hills will get you strong quicker than almost anything else.

That summit is nine miles into the 25.5-mile road. So does that mean the rest is all downhill? Not quite. For sure, much of what remains is downhill, and quite wild too, in many cases--more of our hairball chutes--but there are also several little climbs, just when you think it's going to be all smooth sailing down the mountain. The descent is in the canyon of Big Sulphur Creek. The first mile-plus is a real screamer, on smooth pavement and at well over 10%. After a hard left, the next four miles are downhill at a much more sedate gradient, but on old pavement and with loads of kinky, slinky turns to make it exciting. Don't let the lazy grade fool you: this can be treacherous, and if you let your speed get away from you, you will pay the price. There is one wicked corner where two guys flew off the cliff during the TT and tumbled at least 50' into the rocky gorge. Two different wrecks in two different years, but the same corner each time. Amazingly, both got back on their bikes and finished.

After this long, fun run ends with a crossing of the creek, the up-and-down section begins. There are seven climbs mingled into this final nine-mile downhill run along the canyon. The descents are all longer than the climbs, so you do end up going down more than otherwise. But the climbs take longer, so the overall impression is about even. This is wild country, with the road just barely clinging to the edge of the rocky cliff, occasionally with long, steep drop-offs into the rugged gorge below the road, and hardly a guardrail to be seen. A real walk on the wild side.

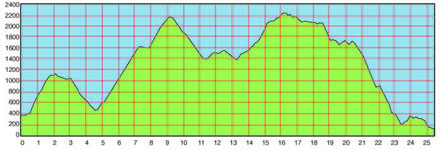

• Mountainview: from Boonville to Hwy 1. 25.5 miles, 3950' of gain.

It really is silly to call roads like Coleman Valley and Fort Ross "small," as I did awhile back. Even more so to refer to the Geysers and Mountainview as "medium." There is nothing medium about these roads. The Geysers is a fierce piece of work, and Mountainview is worse. Speaking about the rigors of Mountainview, a friend of mine once said: "You'll see God out there, and he'll be laughting at you!" I once wrote about it: It's the kind of road that will slap you around, steal your lunch, and hand you back an empty sack."

It really is silly to call roads like Coleman Valley and Fort Ross "small," as I did awhile back. Even more so to refer to the Geysers and Mountainview as "medium." There is nothing medium about these roads. The Geysers is a fierce piece of work, and Mountainview is worse. Speaking about the rigors of Mountainview, a friend of mine once said: "You'll see God out there, and he'll be laughting at you!" I once wrote about it: It's the kind of road that will slap you around, steal your lunch, and hand you back an empty sack."

This is the only road on my list that isn't in Sonoma County. It's a few miles north, in Mendocino County. It's less well-known than some of the roads further south, but if you ever come up on Memorial Day weekend for an ugly cult classic we have up here called the Bad Little Brother, you will have an opportunity to discover it for yourself.

This is a cliché chutes-and-ladders road. There are a number of seriously hardcore downhills, but each one--except perhaps the last one--simply means you're going to have to climb out of the hole into which you just descended.

The North Bay is a land of ridges. Look at a map and you will see very few named mountaintops. We don't have many of those pointy peaks. What we do have is ridges between watersheds. Everywhere. King Ridge, Brain Ridge, Campmeeting Ridge, Bee Tree Ridge, Skyline Ridge, Burnt Ridge, Sheep Repose Ridge, Oak Ridge, Black Oak Ridge, Brushy Ridge...

And wherever the roads go, they have to climb over one ridge line after another. Occasionally they find a way to run along the creeks and rivers, but eventually, inevitably, they decide to hump up over the next ridge. And there we go, we happy gluttons for punishment, following along behind, like Mary's little lamb.

It's difficult to render a blow-by-blow account of Mountainview. It all ends up being the same: hard friggin' work. The scenery, for the most part, is not all that great. (This is in contrast to the other roads on this list, all of which are very scenic, even spectacular.) Except for one or two meadows and a few points with distant vistas, most of the time you're closed in by the surrounding trees, and most of the time, the trees are quite ordinary. There are a few spots with majestic old redwoods, but mostly it's just scrub trees and a dense understory of boring brush. What all that drabness means is that there is very little to distract you from the endlessly tiresome work of grinding up the double-digit walls, mile after mile.

On this road, the chutes really do feel like the chutes on the board game: you work your ass off getting to the ridge, and then you throw it all away on a slide down the chute, and have it all to do over again...and again. The high point on the road--the highest of several summits--is just 1800' higher than the start in Boonville, but the total elevation gain is pushing 4000'...a clear sign you're doing the same thing over and over. Sisyphus would feel right at home here. After having done the road a couple of times, I stopped enjoying the descents much, as I knew what they implied: another climb ahead. Finally, when you get near enough to the coast that you can't see any more ridges between you and the ocean, the road still manages to torment you by throwing little climbs into what should be the final, triumphant downhill...nope...wait for it...just one more little uphill. And then another. It's like someone holding candy out in front of a kid, and when the kid reaches for it, snatching it away.

And then, once you really do get to the longest run of downhill, it's so scary-steep, only the boldest descenders can have any fun with it. 14% for miles and open enough to really let it rip, if you can muster up the brass for it. I don't mind admitting I couldn't do it...not full-tilt...but I've watched others do it, like rocks dropped down a well shaft. The last time I did it, it was raining, and the rims were wet...

No, I find very little to like about Mountainview. And if you do it as any sort of loop ride, it has to be coupled with either Annapolis and Skaggs Springs to the south or with Philo-Greenwood to the north. We'll talk about the roads to the south in a minute, but as for Philo-Greenwood, I can say it's the easier option, and yet it has a huge amount of steep climbing and eleven summits.

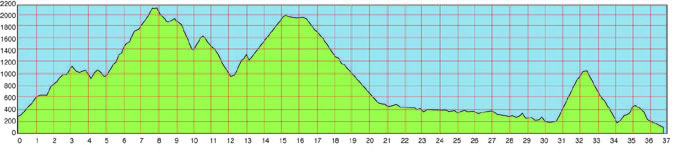

• Skaggs Springs: from Warm Springs Dam to Hwy 1. 37 miles, 5170' of gain.

Here's another road that's a key component in the Terrible Two. The first time I did the TT, I was about two miles up the first climb on this road when a TT vet rolled up next to me and said, "This is the ride...right here." It's the crucial puzzle to be solved.

It's the first thing riders do after the lunch break at mile 109, which means doing it somewhere from early to late afternoon, and because it's on Summer Solstice weekend, it is often hot. Insanely hot, at least if what you're set on doing is climbing one barren, sun-baked 12% wall after another, for the next couple of hours. Because of all of this, I feel safe in saying that Skaggs Springs is probably the most feared road in the North Bay. We call it the Killing Fields.

It has always been a hard road, but it didn't used to be this hard. Used to be, the first section rolled lazily uphill from Alexander Valley, past the old hot springs (a nude hippie haven), and up to Las Lomas, a ghost town in the woods. Then in the early 80's, the Army Corps of Engineers built Warm Springs Dam and Lake Sonoma, right over the old road and hot springs. To bypass the new lake, they routed the road up and over the surrounding ridges. It sometimes seems as if they just drew a pencil line on a flat map and then went out and put the road wherever the line went, without any regard for the topography of the three-dimensional world.

Okay, I know they didn't do that, but the climbs are so steep and so frequent as to seem absurdly arbitrary and capricious, possibly even malicious, at least to a cyclist whose brains have been fried by too much sun...whose bike suddenly weighs 40 pounds and whose quads have turned to wet cement.

The first 13 miles are all on that modern Army Corps road: smooth pavement, wide lanes, guardrails, curbs, storm drains...the works. Everything is as fancy and modern as it can be, and almost every inch of it is steep, both up and down. It is also almost entirely out in the sun. They bulldozed a wide swath for this new road, and few of the oaks on the grassy hills are near enough to cast any shade on the road. We once set a household thermometer down on the pavement on one of these exposed climbs, and it topped out at 150°. Bike thermometers have been seen approaching 120°.

The biggest climb is a fearsome beast, and what almost makes it worse is that you can see the bulk of it from the other side of the canyon as you approach it. I had the distinct, sadistic pleasure of blowing Chuck Bramwell's mind the first time he did the TT by pointing out this daunting wall to him when it comes into view. There is another spot on the Geysers, between its two big climbs, where you get the same sort of horrifying view to the next stretch of climb, and I got him there too. In both cases, he responded with the most gratifying howls of disbelief and anguish...a very satisfactory bit of torment for me.

Mixed in with these brutal ladders are a matching set of hairball chutes. Two are especially noteworthy. They drop very steeply in a series of sweeping bends on that fancy, modern, smooth pavement. Sounds like fun, right? They don't seem too fun to me when I'm on them: too steep and a little too curvy to really let it rip. The Bad Little Brother does this road from the other direction, very late it the day, and these two descents turn into two of the cruelest, leg-breaking, heart-aching, head-baking climbs around.

After those first 13 hellish miles, things get better...a bit. The new road picks up the old road as it emerges from the uphill end of the lake, and then the shade trees reappear and everything seems more pleasant. There is still the rest of the long climb to the Las Lomas summit, but it's never as brutal as what came before. And after Las Lomas, there is one of the best, most entertaining descents around: almost five miles of snaky bends through the trees, never too steep to stop being fun. When the road rolls out in the bottom of the canyon, it runs alongside the Gualala River, and the scenery would not be out of place in a national park, at least some of the time. It's pretty special.

This pleasant, rolling run along the river lasts for about ten miles, and the only bad thing about it might be a headwind, as we're heading west toward the ocean. But all these easy miles cannot deliver us to the ocean. It seems the road could follow the river all the way to the sea, but it doesn't. That would be too simple. Instead, it throws up another of our ladders over another ridge. No, two ridges, but the first one is the bastard. We call this the Rancheria Wall because it ends in a remote Indian Rancheria up on Miller Ridge. It's only 1.7 miles and gains only 900', but those numbers just don't do justice to how painful this climb is.

Someone once wrote little messages on the pavement on this climb, over where a cyclist would ride. You clawed your way around a corner on a brutally steep wall and saw this unreal, even steeper pitch ahead. Right there, down on the ground, it says, "The crying spot." Then the same scenario repeats: another stupidly steep corner; another absurdly steep pitch ahead, and the pavement message says, "The sobbing spot." Finally, the third time it happens, even steeper and more grisly looking than before, the message on the road says, "Not funny anymore!" It got a smile out of me at a point where I didn't think I had any more smiles left in me. A Three-Lament Hill.

After that climb is at last behind us, we have another chute to grapple with, and this one is as gnarly and snarly as any of them, with all sorts of opportunities to come to grief. Super steep pitches, diminishing apex corners, off-camber bends, cattle guards in the middle of diminishing apex, off-camber corners, with hot-tub sized potholes before and after...you get the idea. If you survive it, you cross the Gualala River and have one more, much easier, much more enjoyable climb to do. By now, we're getting near the coast, and the trees all start looking mossy, with ferns underneath, and the air has that damp, salt tang to it that always means the shore is near. It all starts feeling coastal, and then a line of blue appears through the trees ahead and the ocean is there. We made it! The Killing Fields are behind us once again. In the context of the Terrible Two, we would have 50 miles and the big Fort Ross climb ahead of us, but it still feels like a victory to finish with this implacable road.

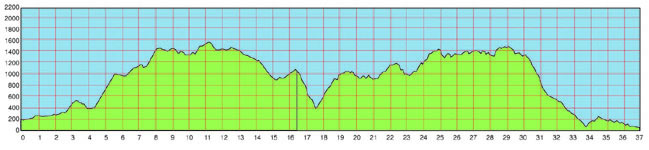

• King Ridge, etc: from Cazadero to Jenner. 37 miles, 5300' of gain.

Most folks have heard of King Ridge. Many consider it the crown jewel of North Bay roads. But it's only 16.5 miles and this segment is listed at 37 miles...? That's because it's impossible to think of King Ridge without seeing it within the context of the other roads that make up this classic chutes-and-ladders loop: Hauser Bridge, Seaview, Meyers Grade, and a little section of Hwy 1, to where the serious ups and downs end in Jenner. 37 miles won't close this classic loop, which is 55 miles by the shortest course. But the other 18 miles of roads that do, along the Russian River and Austin Creek, are nearly flat and of lesser interest to us today. Today, we're just doing chutes and ladders. Flat stuff need not apply.

King Ridge begins in the town of Cazadero, at the same junction where Fort Ross Road departs (or ends, as we have it drawn up here). The first two miles are a pleasant, rolling cruise along Austin Creek. The first climb is a little one of about half a mile. After a small but busy descent back to the creek, the hard work begins with a really brutal climb of 1.3 miles, at which point there is a clear summit. A mile of easy, slightly uphill rollers leads to another very stiff climb of just under a mile. At this point, we've reached the real world of King Ridge... the part that everyone raves about.

Although there are several more significant climbs ahead, for the most part now, we're riding along the ridge line, with views off one side or the other. At one point, the road tiptoes along a spine of ridge just a few feet wider than the narrow road. There are panoramic views off both sides of the road at once: to the west out over the far, blue Pacific, and to the east spanning rank on rank of empty, serried hills. Sometimes we're riding through woods of redwood, oak, and bay laurel, and sometimes crossing open meadows of waving grass. Every inch of this ride is beautiful, but up on the ridge, the vistas are so stunning, so transcendent, even the most hardened hammerheads slow down and gaze in awe. This is it: purest bike heaven. This is why we ride.

In addition to all the buffed-out climbing one does on King Ridge, there are also a number of exciting descents. If we were riding this road in the opposite direction, our cyclometers would record 1400' of elevation gain, and for us that translates into 1400' of twisting, slinky fun.

Eventually, King Ridge ends at a junction with Hauser Bridge Road and Tin Barn Road. Tin Barn, to the north, connects to Skaggs Springs, and on the way there does more outrageous chutes-and-ladders capers. But we're going south and west on Hauser Bridge. Over the next 22 miles, the road will change names from Hauser Bridge to Seaview to Fort Ross (a brief snip of it) to Meyer's Grade without really making any turns. It's all good stuff, whatever it's called. Hauser is one of the most extreme chutes in the region: a wild, corkscrew, one-mile, down-the-rabbit-hole free-fall, culminating in a 20% plunge to a one-lane, iron-grate bridge over the Gualala River. (It was here that pro Alexi Grewal rolled a sew-up off the rim in the Coors Classic, prompting his colorful assessment of the conditions: "Fucking scary!") Pavement on this descent ranges from mediocre to dreadful, so you really have to treat it with respect. An authentic 20% pitch with loose gravel, potholes, and tree roots buckling the pavement is a serious piece of work.

After the bridge, we have to climb back out of the canyon into which we just dropped...a steep pitch of 1.7 miles, followed by five miles of more moderate ups and downs (mostly ups) along Seaview, where we hardly view the sea at all. This leads to a junction with Fort Ross Road, coming up from the coast. We merge onto Fort Ross and, half a mile later, the other portion of Fort Ross turns left toward Cazadero and we continue straight on Meyers Grade.

Throughout the climbs on Hauser and Seaview, we've been riding in the trees--close-up scenery without any panoramas--but once we hit Fort Ross and Meyers Grade, we emerge onto a ridge above the ocean with views to forever. For me, this is almost as wonderful as King Ridge. It's not as long--only five miles, as opposed to 16--but it makes up for it with silky-smooth pavement and stunning views. On a clear day, you can look all the way back down the coast to Tomales Bay and to Mt. Tam in the far distance. But you may forget to notice the view, once you begin the hair-raising 16% downhill chute to Hwy 1.

This is a really thrilling ride. You're screaming downhill, thinking, "Boy, this baby is steeeeep!" and then you fly over a ledge and it gets even steeper. You think it can't possibly get any steeper, and then it does the same thing again...and then again! And the beat goes on when you turn onto Hwy 1, with another couple of miles of descent so dizzily twisted the locals call it Dramamine Drive. The grade on Hwy 1 isn't as steep as the pitch on Meyers Grade, but is probably more fun because of that: you can really let it all hang out. If you encounter any traffic on the busier highway, it's just as likely that you'll be passing the cars as holding them up. You drop all the way to the beach, climb a small hill, and then traverse the cliff face above the crashing surf, arriving in a couple of miles at the mouth of the Russian River and the town of Jenner, which is where the chutes-and-ladders section ends and the road flattens out.

Did you notice that all of the roads on this list--except for the Geysers--tee into Hwy 1 along the coast? All of the best (worst?) of this wickedly hilly action is in amongst the steeply folded ridges that constitute the last ramparts on the edge of the continent: the coastal hills. There are other chutes-and-ladders roads further inland as well. (I could have made this a Dirty Dozen list instead of a Half-Dozen, including perhaps Oakville Grade-Dry Creek-Trinity Grade, which will be in the Tour of California this May.) But the ones that seem the most extravagantly steep and sketchy--the ones that have you looking again and again at your derailleur, hoping for another gear--are mostly out here on the ragged fringe of the land mass.

Chutes and Ladders. Three-Look Hills. It's what we do here. No one would ever confuse these pesky little pitches with the Alps, but a lot of pros choose to train here in the winter to prepare for the Alps later in the season. Those of us who live and ride here all the time aren't training for anything. We're just out there, soaking up the scenery, delighting in the downhill dancing, chugging up the walls, and every so often stealing glances at our gears, just in case we missed one the last time we looked.

Bill can be reached at srccride@sonic.net